There is no attempt to communicate anything in particular, as there is no determinate meaning. That is to say there is no content positioned by analogy, allusion or metaphor, by intended association and connotation. That is not to say there is no meaning, rather the intention is in the random choice of found objects that are rematerialized; cast in different materials and reproduced in photographic form. These found objects have been rejected, discarded, simply thrown away as refuse, or remnants of a previous purpose; in short they are now useless.

The process of rematerialisation is also one of dematerialisation. The mould is made from the found object, an imprint is left in the negative; a hollow space where the found object momentarily rested. The mould seems to record this trace, but it also describes an absence, a loss. In the space of absence, the found object also loses its materiality; it becomes a void, solely mapped by a surface of silicon rubber. This surface is an interior one, with no relation to the outside form of the mould. Here we have a textural imprint that is illusive and without an apparent readability.

The mould is a kind of text that operates in the linguistic realm of the ‘shifter’: it only makes sense in the context of what it is supposed to utter, to produce. In the Lacanian sense if the mould operates as an ‘indexical signifier‘ (shifter), it is split between its stated function (to reproduce something) and its action of production (enunciation). The ‘I’ of the indexed author is similarly split as in the textuality of the mould. When one views the split subject as the shifter at work (enunciation) within a particular context (this writing under a pronoun), there is a relation to the duplicity of the mould as a site of a reproduction, while maintaining its unique ‘objectness’. In other words, the mould states its purpose as a very particular and determinate one. Yet as it is the obscured internal surface that is the only reason for its existence, the enunciation is what is produced from the mould: the negative space of the mould is fundamentally split with the positive object that is produced. They can never be reconciled, though they are co-dependent.

We therefore have in the mould an object that is both indeterminate and highly specific in its function. It is an object that is produced to facilitate a constant production (enunciation). It is the object par excellence as an indexical signifier; a shifter for the enunciation of other objects.

Have I placed too much import on the mould? I think not in textual terms, as the mould is another moment in intertextual production, and a particularly important one. Bearing in mind that the found objects chosen are also produced with moulds of the industrial kind; metal dies. It is the mass produced prior life of these objects that is perpetuated in the fine art mould making and casting process. The perpetual textuality of these objects again privileges the role of the signifier in a continuing process of movement; the play of the signifier.

The mould enacts a kind of displacement, if you like a splitting in production. What comes out is a rematerialisation of a prior object that seems at once indexed and dislocated; the copy that moves on from prior signification. This is the possibility of the signifier to be released from its normative (conventional function). It is also the moment when the essence—if we can momentarily locate something akin to a distilled production—may reveal or precipitate a multiplication of signifiers. We have at once a moment of truth, and its immediate supersession by multiples of meaning and connotation. (Though the moment of truth may in fact derive from the connotations, there is no linearity in this process.)

When Roland Barthes identifies connotations in the writing of Cy Twombly’s work, he is similarly searching for the moment when the text ruptures and releases itself into a multiplicity of fragments. A particular reading is contiguous with the found objects that populate this research practice:

A paradox: the fact, in its purity, is best defined by not being clean. Take an ordinary object: it is not its new, virgin state which best accounts for its essence, but its worn, lopsided, soiled, somewhat forsaken condition: the truth of things is best read in the cast-off. [1]

Though Barthes is not referring to cast objects, the relation between the cast-off object and the casting of cast-off objects is hardly opaque. Thus, if the cast-off object is recast, rematerialized in its forlorn, discarded state, there must be an attempt to add value or at least reveal the value in this ‘forsaken’ object. Is it the object that is receiving value in its rematerialized form, or the text that surrounds, bringing this object into a different sign system? The textual field of the art object is indelibly infiltrated with resonance, association and allusion; we expect to be able to interpret something, to read meaning into something.

We cannot escape meaning, for signs are the way we decipher the world, make sense of it. These cast objects are but signifiers in this process, the process of the text as it weaves its litany of possibilities for writing. However, these objects also attempt to highlight their textual intentions. There are no messages to be found, but there is the implicit prompt for the reader to ‘make something of them’, to write a text, to project something onto the object as Other. (The inanimate object can also function as a kind of Other) It is up to the subject position of the reader to employ whatever syntagms and paradigms they wish to construct or invent; metynomy and metaphor are tools at the readers’ disposal.

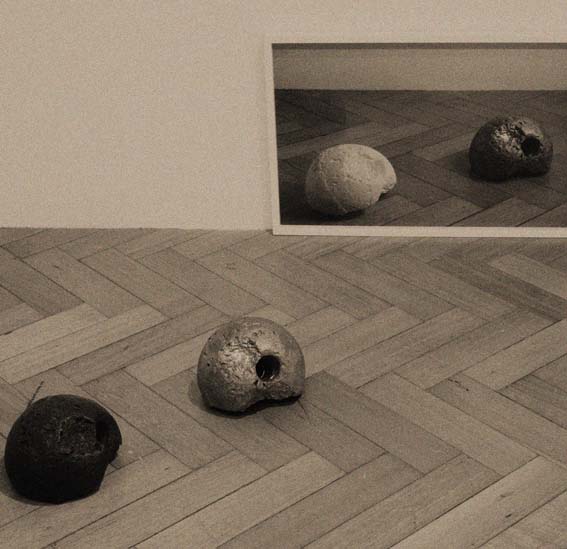

This inanimate object must be recognised as thoroughly textual. It is derived from previous texts, it is contiguous (intertextually woven) with whatever its context of writing may be: its site and means of display, its reproduction in photographic form, the words that are written or spoken about it etc. It is also textually imbued with social, economic and art histories. As a fragment that is found and then cast, reproduced in photographic form and written and spoken about, this object is non-specific in the sense that it is part of many texts that cannot be particularised. It is a supplement in the Derridian sense because its is the product of a larger discourse, of systems of language to which it is both part of and separate to, as Derrida succinctly notes: ‘Its place is assigned in the structure by the mark of an emptiness’.[2] It is inside and outside these structures because it functions in both its absence and presence; it is premised on a web of productions: a prior object that falsely suggest an origin, the origin that is translated (‘translation augments and modifies the original’[3]) into another material through the absent space of the mould. Yet the so-called original also existed in a prior state (another material text) that was moulded. Further, the photographic text proposes its absence again (‘flat death’) as another supplement. To what? And so the centre is lost, or rather there never was a centre. We have the affects of the supplement, yet it never had an absence or a presence, only an affect, a virulence.

In this reasoning it is the text as an object that is the ‘dangerous supplement’. It is the object that is always missing, the object that its traces adhere in ghostly shadows. And these marks, the affects of its absence, the texts that hover around it are the remnants of the supplement; the bits of text that suggest something else; something that escapes the object, identifying its permanent and unresolvable state of dislocation.

[1] Roland Barthes, The Responsibility of Forms : Critical Essays on Music, Art, and Representation (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991), 122.

[2] Jacques Derrida, Of Grammatology, Corrected ed. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998).

[3] Jacques Derrida and Christie McDonald, The Ear of the Other : Otobiography, Transference, Translation : Texts and Discussions with Jacques Derrida (New York: Schocken Books, 1985).

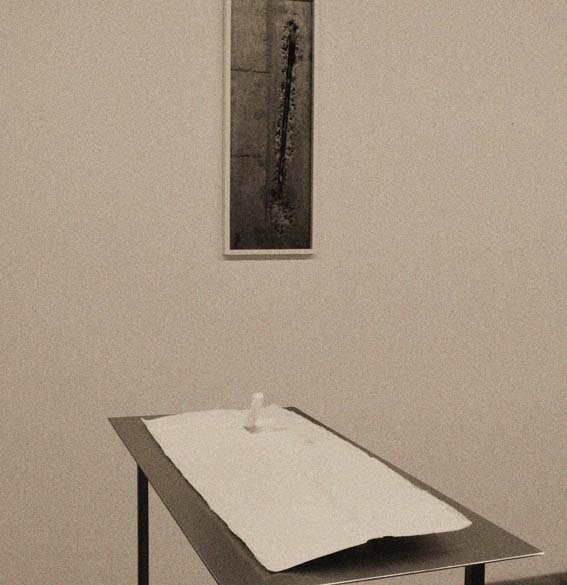

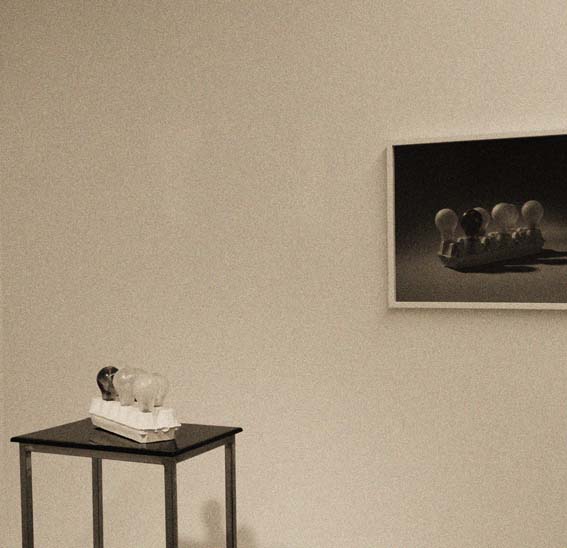

Alas, Therefore, Thus, 2011-12, patinated bronze, 18ct gold, human hair, lead, polyurethane resin, silicon rubber, glass, stainless steel, inkjet print on rag paper

The photographic text may continue….